War is no fun, but there’s a lot to write home about

By Cinda Ackerman Klickna

What did the Civil War soldiers from Illinois write home about? Enlisting? Camp life? Love? Battles? Sickness? Prostitution? All of these and more.

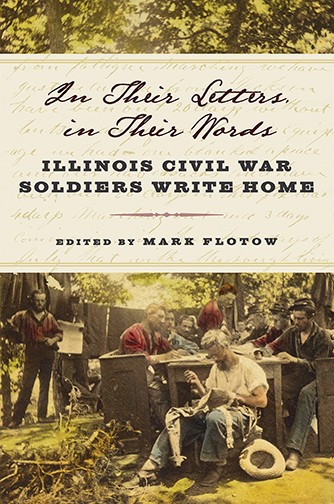

Mark Flotow of Springfield, an independent researcher, is retired as the director of the Illinois Center for Health Statistics and currently serves as an adjunct anthropology research associate at the Illinois State Museum. He began reading soldiers’ letters, housed at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, due to his interest in the Civil War. After a few years he realized the stories told by these soldiers needed to be compiled. Thus we now have an amazing collection of our Illinois soldiers’ thoughts and firsthand accounts in Flotow’s book, In Their Letters – In Their Words – Illinois Civil War Soldiers Write Home. The book includes 533 quotations from letters written by 165 soldiers between April 1861 and December 1865. Illinois had over 259,000 soldiers, the highest number per capita of any state. Many mustered out of Camp Butler near Springfield. Their median age was 24.

In Their Letters – In Their Words – Illinois Civil War Soldiers Write Home, by Mark Flotow. SIU Press, 2019, 302 pages, $26.50. May be purchased at Books on the Square, Barnes and Noble, online at SIU Press or at markflotow.net.

Millions of letters were written during the Civil War. Mail was important to the soldiers. “The mail is watched with anxiety and the soldier’s heart leaps for joy when he hears his name called at the distribution of the mail,” wrote one soldier. Another said, “Your letters are worth more to me than gold.”

At a recent presentation about his book, Flotow asked participants to comment on a letter that he had projected on a screen. “Neat,” said one. Another said, “No punctuation, poor grammar and spelling.” And another shouted, “In cursive, which kids today don’t know.” Flotow agreed with all. Soldiers filled the page because it was often considered an insult if the writer didn’t use all available space. Very little punctuation was used, and letters are riddled with misspelled words. Many are neatly written, which is surprising as the soldiers would often use a tree stump or their knapsack for a writing surface. Flotow emphasized that every letter he read was written in cursive.

About 90% of Illinois soldiers were literate. They fought throughout the South and, as Flotow says, “never thought their letters would be read today; they were merely writing home.”

Flotow explained his process for compiling the selections. “The soldiers were like informants. I asked – how did their words reflect on the war?” He then researched topics to add historical context to the comments in letters. So, we come away from the book learning not only about the Civil War but also factual data from the period, specifics about a battle, mail delivery in the U.S., weather patterns in certain locations, diseases and names of ailments that today aren’t used, field hospitals, etc. The letters are arranged by topics.

“I know the principles that we are fiting for are write,” wrote Josiah Kellogg (Warren County) on May 9, 1863. He was killed the following May. We experience uneasiness in reading Elmer Ellsworth’s letter to his wife (Winnebago County) dated May 23, 1861: “We are to cross the river…one is somewhat likely to be hit…if anything should happen, darling…the highest happiness I looked for on Earth was a union with you.” Many letters, like this one, make the reader wonder what happened to the writer. Flotow has added a short biography of each soldier that helps humanize each person and sometimes makes one pause and view their letter in a new light. In the biographical sketch of Ellsworth we learn he came to Springfield in 1860 to study law and worked on Lincoln’s presidential campaign. He was killed the day after he wrote to his wife.

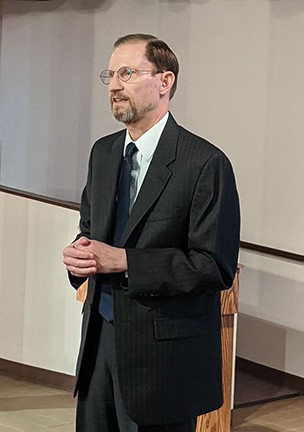

Photo by Bill Lear, ISMM

Mark Flotow gives a presentation at the Illinois State Military Museum, Jan. 11 2020.

Soldiers faced diseases such as scurvy, diarrhea and what today we call post-traumatic stress disorder. They had to deal with fleas and lice, mud and rain, frostbite and sweltering heat, rationed food and bitter coffee. They watched their fellow soldiers die on the field or have a leg amputated. They watched some soldiers run from battle or be taken prisoner. All of these topics are shared in detail in their letters.

Most of the soldiers had never traveled far from home. An entire chapter is devoted to their views of the Southerners and slaves. David Norton from Cook County writes on Aug. 24, 1863, of talking with a Southern lady who didn’t believe he was a Yankee. “When I asked why she didn’t believe me she replied she had been told that a real yankee had but one Eye…in the middle of his forehead and that some had horns on their heads like cattle.” Another says the Southern farmers, known as planters “are ignorant enough.”

There were opposing views of slaves. Jonas Roe (Clay County) writing on July 15, 1863, to his wife says, “Many of the Slave owners do not treat their Slaves as well as we treat our horses and Cattle.” Writing from Tennessee on April 24, 1862, James Haines (Sangamon County) tells his brother, “I hope you will not get offended at me for writing my sentiments…for hateing the plaguey Negroes…I hope you will think alittle more of your own race.”

The letters give an insight into every aspect of their daily life. Some are uplifting and full of hope and love, others, disturbing and focused on battles and harsh views. Flotow’s book is masterfully arranged and provides a unique view of the Civil War.

Cinda Ackerman Klickna found the letters quite interesting and plans to visit the ALPLM to search for letters from Civil War soldiers buried in a small cemetery in Tazewell County where her relatives are buried.