Susan Lawrence Dana was more careful with money than you think

Photo by Doug Carr Dana-Thomas House State Historic Site at 301 E. Lawrence Ave. has experienced a steep drop in its number of annual visitors.

Eyes downcast, with a guilty expression and in a quiet voice, a friend of mine admitted, “I have never been through the Dana-Thomas House.”

She isn’t alone; too many have been missing out on a Springfield treasure – not only in seeing the stunning interior with its amazing art glass and furniture, but also in learning about its architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, and its eccentric owner, Susan Lawrence Dana.

Regina Albanese, the executive director of the Dana-Thomas House Foundation since 1998, says, “We don’t have royalty in our country, but we have wealthy people who have made an impact. There is the Hearst Castle and the Biltmore estate. Yet, here in Springfield, we have the Dana-Thomas House. Susan was a wealthy woman who made a huge impact on our city.”

Recently, the Dana-Thomas House Foundation received a collection of documents from Springfield attorney Daniel Greer. As a young lawyer, Greer joined the law firm of the elderly Earl Bice, the attorney who had represented Susan Lawrence Dana in the 1940s. Bice had kept many records and over the years had told Greer stories about Susan

In the collection are receipts for purchases Susan made in many corners of the world, letters (some are obvious love letters) and Susan’s account books. Hundreds of items shed new light on some previously believed facts, and yet raise new questions. All have been catalogued.

Susan Lawrence Dana

At the corner of Lawrence and Fourth streets, the 12,600-square-foot home was designed by Wright in 1902, with Susan stipulating that the original parlor in her parents’ home be kept intact. He preserved the parlor, but also created rooms that cover an entire block, wind around through 16 levels, and include intimate fireplace areas as well as large spaces for entertaining.

The house in Springfield is considered the most intact of all of Wright’s designs. It has more than 100 pieces of furniture designed for the house (including a dining room table that seats 40), and over 450 pieces of art glass in windows, light fixtures and ceiling panels. And, of course, all love to see the one-lane bowling alley in the basement which, Albanese says, “is believed to be the only house that Wright designed with a duckpin alley.” Duckpins are smaller than regular bowling pins.

Much has been written about the house and Susan: the preservation of the house from a demolition crew; the $8M restoration done in the 1980s; Susan’s flamboyant life of world travel, amassing a lavish collection of jewelry, tapestries and over 5,000 books; the five-day sale of all of her items in 1943 when she was elderly and living out her days at St. John’s Hospital; her three husbands, one who was 14 years younger than her; the parties she hosted with up to 1,000 guests; her work for education funding, women’s rights and African-American equality.

Many believe Susan Dana had opened her checkbook to Wright. But one receipt in the newly acquired collection shows she was more particular about costs than first believed. There is a four-page list from the Linden Glass Company in Chicago with each item checked off and marked OK with Susan’s initials. The list gives insight into the items in the house, such as yards of cloth ($7.50 a yard), pillows, upholstery work, and identifies the location of items – library cushion ($27), 4 panels music room cabinet ($32), three pieces of Korah silk for the bowling alley ($54). More expensive items listed include the beautiful art glass lamps: 2 Double standard lamps, $150, and 2 Double standard lamps special shades $200.

Susan questions a bill for glass in the newel lamps, and Wright has written back to her, handwritten over her note, “This bill is for the glass in the newel lamps one of which goes on post by bowl in your bathroom.” Signed with Wright’s initials.

In another receipt Wright has addressed his note to Mrs. S.L.D.

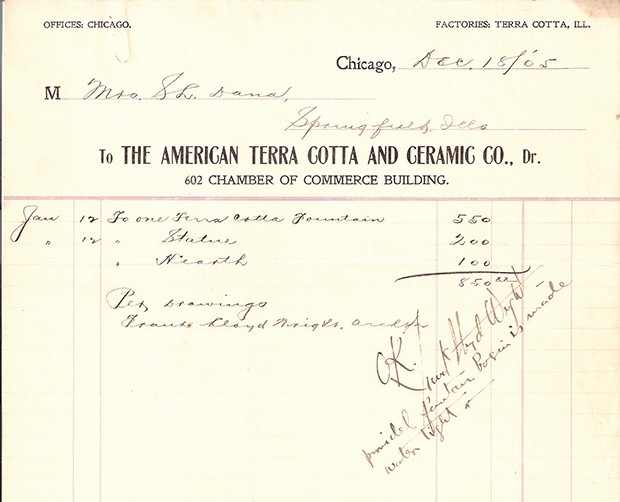

The house includes a terra cotta stone fountain called Moon Children. Within the documents we now know how much this cost – a receipt from the American Terra Cotta and Ceramic Company in Chicago for the fountain ($550), statue ($200) and hearth ($100), “per drawings, Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect.” Wright has clarified with a note under his signature, “provided fountain is made water tight.”

Susan had also commissioned Wright to design the library in the Lawrence School, now the Lawrence Education Center. The library honored Susan’s father, Rheuna Lawrence, who had served as mayor of Springfield, president of the school board, and was a prominent member of Springfield society. A handwritten receipt to the American Monolith Company in Chicago, dated Jan. 27, 1906, and signed by Susan, reads, “Enclosed please find my draft for one hundred and ninety-seven dollars, fifty cents for floor of Lawrence Library.”

One of the most interesting stories about Susan was that she purchased a baby’s layette set in Paris on her honeymoon with her second husband. Susan was 49; her new husband was 26 (although their marriage license lists her as 36!). Susan had lost two infants born during her first marriage to Edwin Dana (he was tragically killed in a mining accident). In the donated items is the actual receipt for the layette, listed in French francs. And, sadly, there is also a small plastic bag holding a lock of Susan’s hair along with locks of hair of her two sons, one who died after a few hours; the other who only lived two months.

Some items give insight into Susan Lawrence Dana’s wealth. Small 4×6 ½ account books prove that Susan not only bought lavishly, but that she actually loaned money to businesses and people in Springfield, earning interest on these loans. She earned rent on downtown buildings that she owned. There is a record from 1903 that she sold bonds, believed to be for the first YMCA.

Page after page in account books – four in all in the donated items – lists income from her various investments. One entry raises lots of speculation. It documents a loan to Frank Lloyd Wright and his wife in 1903, “due Aug. 15, 1906,” for $4,615.25. But Susan paid off the principal before the full payments were due. It is known she helped bankroll Wright’s sisters’ school in Wisconsin so it isn’t surprising she paid off a loan to her great architect. But why? Could it have been in exchange for the drawings of the house or the Lawrence Library?

Then there are 39 letters, written between the death of her first husband and marriage to her second husband, from Howard Dudley, obviously an admirer of Susan’s. He invites her to visit him out west and offers “a nice easy ride about the Valley in my new Packer.” Although none of Susan’s correspondence to Dudley exists in the collection, his comments give some insight into a relationship that may have been more than platonic. He thanks her for a ring she made for him, and comments on the great time they had together.

Albanese says, “We have acquired other items throughout the years. A prior board member found a set of vintage duckpins for the house and donated them. We have been able to purchase all three of the missing fern stands from Westminster Presbyterian Church in Springfield. In 1998 one of the original hand-hammered copper urns was purchased. So, the house today is really very complete. If there were two of something we have at least one and in many instances all.”

The foundation is awaiting furniture that is being donated back to the house. The Master Gardeners have been restoring the gardens after a construction project in 2011, followed by two years of drought, destroyed the plantings.

“We are open seven days a week,” says Albanese, “and people still think we are closed due to the state’s revolving decisions to open/close/open the home in the past few years. That has had an impact on our number of visitors. We have seen a decrease from over 40,000 during the 1990s to now around 22,000.”

The Dana-Thomas House is a treasure in our city, and all should come see the amazing house and its spectacular furnishings, learn about a woman who blazed the trail for women and minorities, and experience an architectural wonder, known throughout the world.

Cinda Ackerman Klickna started writing articles on the Dana-Thomas House and Susan Lawrence Dana during the 1980s. She is fascinated by the stories about Susan. This article can’t begin to tell all there is about this independent and colorful woman.