Springfield reacts to a pandemic

By Cinda Ackerman Klickna

There are stark similarities between the coronavirus pandemic and the 1949 beginnings of the polio pandemic in Springfield.

Then, as now, the length of isolation was set at 14 days; people were urged to stay away from others and practice clean hygiene. There was a call for nurses to help with the increase in hospital patients. Some patients had to be given help with breathing, although through an iron lung rather than a ventilator. The polio virus hit hardest among those who lived in poor conditions and poor sanitation — in Springfield the east side of town was affected most. Events were canceled, and the media began offering more programs. Parents had a hard time keeping their children entertained and engaged. And, people hoped there would be a vaccine soon.

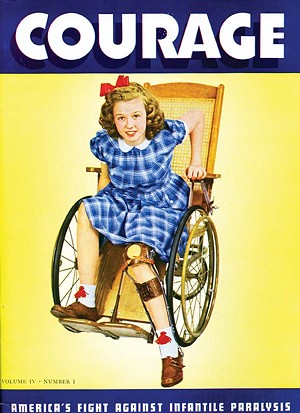

IMAGE COURTESY SANGAMON VALLEY COLLECTION A 1943 publication of theNational Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. There are stark similarities between the coronavirus pandemic and the 1949 beginnings of the polio pandemic in Springfield.

Then, as now, the length of isolation was set at 14 days; people were urged to stay away from others and practice clean hygiene. There was a call for nurses to help with the increase in hospital patients. Some patients had to be given help with breathing, although through an iron lung rather than a ventilator. The polio virus hit hardest among those who lived in poor conditions and poor sanitation — in Springfield the east side of town was affected most. Events were canceled, and the media began offering more programs. Parents had a hard time keeping their children entertained and engaged. And, people hoped there would be a vaccine soon.

The polio epidemic had one major difference. It hit children, not adults. So, when the quarantine went into effect in July 1949, children under the age of 16 were the ones most impacted. Since children were out of school for the summer, keeping up with lessons wasn’t needed.

The first polio case reported in Sangamon County was on July 11. The victim was Betty Ann Ferree, 14, who lived in Springfield at 1618 E. Edwards.

In Springfield the first fatality occurred on July 18 with the death of Joan Angela Lewis, age 12, who was an eighth-grader at Matheny school. Illinois reported 80 cases across the state.

Since St. John’s Hospital was a regional center, patients were brought from other towns to the ward set up for polio patients. On July 21 the State Journal appealed for more nurses.

Just as there is no known cause of the coronavirus, the cause of the polio virus was a mystery. There were several theories posed: uncontrolled weeds, swimming pools and flies. The health department issued a statement July 23 that the pools and beaches were safe and sanitary. The city council mandated that residents needed to remove weeds; homeowners would be charged for the removal. Pesticide was sprayed to try to cut down on the fly population. Later, it was reported that none of these had much effect on the epidemic.

Later it was learned that the polio virus was actually caused by infection through mucus or feces. The poor sanitation and sewer system, as well as many outhouses, were blamed after research determined the real causes.

The July 30 headline in the Illinois State Journal read, “Pray, spray and shy away.” A quarantine was issued by the city’s superintendent of health, Dr. J.H. Shamel. All children under the age of 16 were to be confined to their homes and required to stay in their own yards. All swimming pools were closed, and children under 16 were forbidden to enter a movie theater. Children could be taken for a car ride to have distraction, and appointments such as a doctor’s visit were allowed.

The quarantine was to last 14 days, but people were warned that if cases continued, the quarantine would be extended. Immediately, events were canceled as people stayed home. Picnics, ice cream socials, Sunday school classes and summer camps were halted.

Parents had to find activities to keep their children engaged and entertained. WCVS and WTAX radio stations started children’s programs to help children pass the time. Many groups held polio fund drives to raise money for help and research.

A section of the daily newspaper was called the Junior Journal and Register, geared for the young. On July 31, youngsters were urged to send in their entries for the hobby contest. The paper wrote, “Since you are quarantined to your home due to the polio epidemic, you have plenty of time to get your exhibit ready.” The exhibit would be held later at the Centennial Building.

The Illinois State Fair had fewer visitors that year. Since Springfield children were under quarantine they could not attend, but children from other cities with no quarantine could.

Most felt the quarantine was warranted but were happy when it was lifted on Aug. 24. When the quarantine had been invoked the city had seen 16 cases and 2 deaths. When the restrictions were lifted, 58 cases and 10 deaths had occurred.

The next week was school registration, so school started on time.

Polio cases continued to occur throughout the next few years.

It was another six years before a vaccine was found. In 1955 Jonas Salk discovered the polio vaccine, and that year 1,100 first and second graders were given the vaccine in several schools in Sangamon County.

Cinda Ackerman Klickna of Rochester is a freelance writer who often contributes to Illinois Times.